by Joel Salatin, Plain Values

Last month I introduced the concept of the carbon economy for soil fertility and the numerous ways God designed soil fertility and development to run on sunbeams converted to biomass. From bison on the prairie to wildebeests on the Serengeti, perennial prairie polycultures pruned by herbivores chased by predators built the deepest and most fertile soils on the planet.

That’s the big picture, but how do we apply it to our gardens and farms? How do we catalyze on-site carbon development and utilization to build the organic matter by cycling biomass into the soil?

Sir Albert Howard introduced the scientific method for aerobic composting with a five-part recipe: carbon, nitrogen, water, oxygen, microbes. When those are in correct ratios, rapid decomposition occurs. If any is out of balance, the decomposition either halts or moves in less desirable directions, like putrefying or stagnating.

While composting is human-managed for rapid decomposition, natural processes practice decomposition without manipulation. We see this process routinely, like when a tree falls in the forest and rots over time. If that same tree falls in a pond, however, it won’t rot. Why? No oxygen.

Perhaps the most vibrant ongoing decomposition occurs in pruning. A plant wants to maintain biomass equilibrium between what’s above the ground and what’s below the ground. Plants try to maintain bilateral symmetry at the soil horizon. In other words, if you could see below the soil surface, you would see as much plant material below ground as above ground.

Pruning above ground makes the plant jettison root mass to maintain equilibrium with above-ground material. Nothing expresses this more dramatically than forages when they are mowed or grazed. When you cut off the top of a grass plant, for example, it sloughs off an equivalent amount of root mass for two reasons. First is to keep the plant from having to maintain far-off appendages while recovering from pruning shock.

When you buy a two-year-old apple tree from a nursery, what does it look like? A stick. Why do they prune off roots and branches? If the plant has to maintain those roots and branch twigs while going through transplant shock, the energy drain on the plant’s core will either set it back or kill it. In similar fashion, the grass plant protects its core when it’s pruned, just like your body protects the liver and heart when you go into shock. The body shuts down fingers and toes first; all this protocol is about preserving life.

The second reason the plant jettisons root mass is to capture that carbohydrate energy, concentrating it in the core of the plant to send forth new shoots. When pruning, either mechanically or with an animal, the plant’s solar array (leaf area) diminishes, and it calls on stored energy from the crown, or core, to send out new leaves. This temporarily weakens the plant until the leaf area gets big enough to run on its own power and then replace the energy and roots lost during the pruning process. We call this pulsing the pasture, like a heartbeat.

When plants begin to grow, or re-grow, they follow an S-curve, starting slowly, then speeding up, and then slowing down toward senescence. I call these three stages diaper grass, teenage, and then nursing home. Unlike humans, grass goes through all these stages in as little as 50 days. Keeping the plant in that rapid teenage growth cycle as many days as possible is the key to converting as many sunbeams as possible into decomposable biomass.

The foundation of soil carbon, then, is this root mass injection that comes from strategic pruning. The migratory choreography of wild herds ensured that pruning and rest cycles maintained this heartbeat, or pulsing, in the soil ecosystem. Obviously, either over-pruning (keeping the plants too short) or under-pruning (leaving the plants in a senescent state) shuts down the solar panel and carbon collection. Every hundred pounds of grass is only five pounds of soil; ninety-five pounds is pure sunlight. Under good stewardship, the planet should be gaining weight every day with all the conversion of sunlight into biomass. As farmers and gardeners, that is our mandate.

On our farms, we mimic this pulsing with what I call “mob stocking herbivorous solar conversion lignified carbon sequestration fertilization.” That means we restrict the animals to small areas, moving them every day or two to a new paddock, allowing the forage to recuperate to almost senescence before putting animals back on the area. And yes, this applies to one cow and one horse. In my experience, much of the worst grazing in the world occurs on homesteads and small acreages with only a handful of animals. When they aren’t rotated, the forage can never build root mass which means the soil can never receive its carbon injection.

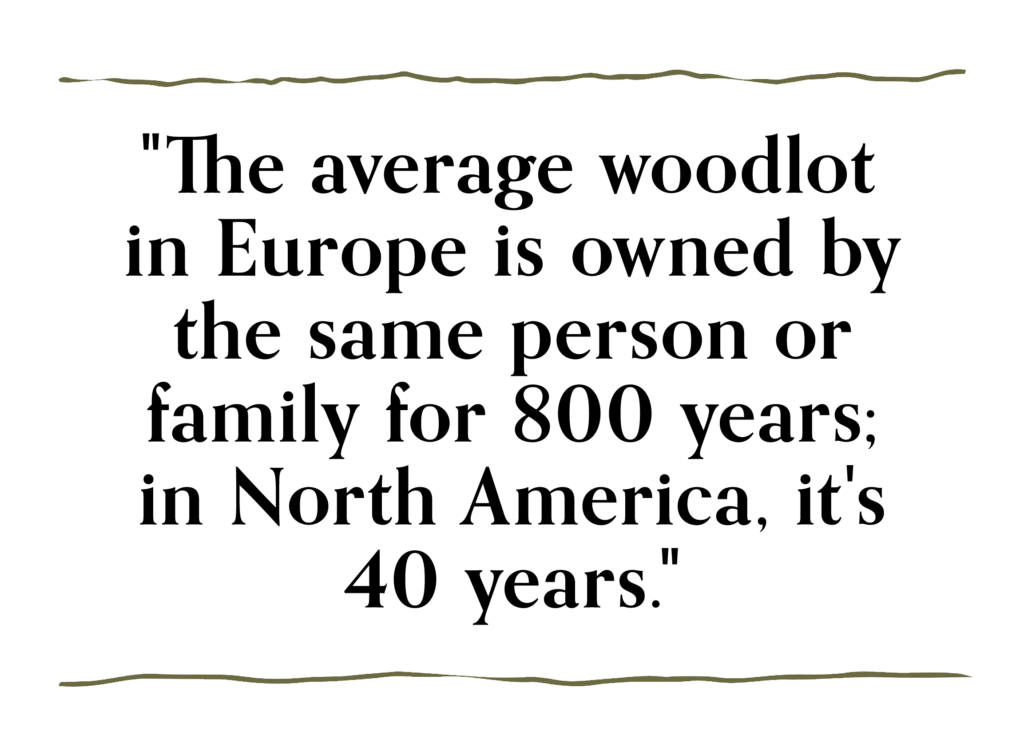

The next carbon source on the farm is the woodlot. One of the most overlooked and mismanaged portions of a typical farm is the woodlot. I asked an Austrian forester one time why the European forests were significantly more productive than North American.

His quick answer startled me: “Royalty.” I was taken aback. He explained: “The average woodlot in Europe is owned by the same person or family for 800 years; in North America, it’s 40 years. You can’t have a forestry plan with a 40-year ownership turnover cycle.” Managing a woodlot requires visioning far into the future, and in this column, I’m not going to dive into the nuts and bolts of silviculture. Suffice it to say that forests need pruning, culling, and management, just like livestock and forages. Native Americans managed with fire as their most strategic tool. That culled out the diseased, weak, and undesirables. Thick, dark woods are a fairly recent American phenomenon created by fire suppression policy.

Weeding a woodlot does not diminish its overall production; it simply concentrates the growth on desirable stems. An acre can only grow a certain amount of material; the goal is to put that growth on desirable stems.

That means American forests, especially east of the Mississippi, have incalculable tons of biomass retarding growth on good trees. One of the first big equipment investments we made on our farm was a commercial chipper. That machine enabled us to generate our own carbon and at the same time upgrade our forest acreage. The sheer volume of carbon that can be generated by even one acre of woodlot weeding is unbelievable.

When I say “we don’t spend any money on fertilizer,” it doesn’t mean we don’t invest in soil development. The chipper, labor, and fuel are our fertilizer investment. Since coming to the farm in 1961, when it averaged one percent organic matter, we’ve moved the soil to more than eight percent organic matter. While organic matter and carbon are not identical, they are close enough cousins for this discussion.

If all money currently invested in chemical fertilizer were invested instead in carbon development, we’d have healthier and more productive forests, much healthier soils, and fewer (if any) fires. Had we as a nation been managing our forests correctly for the last hundred years, the fire conflagrations costing us many billions of dollars annually could be eliminated and all that biomass dedicated to soil building. Wouldn’t that be a good exchange?

Most farms have a patch of woods or woodsy areas that scream for management. A balanced farm should be at least 25 percent forest and up to 5 percent water (ponds). All ecosystems thrive at the intersection of forest, open, and riparian edges. A chipper and chainsaw are the best tools to manage trees.

Woodlots offer standing carbon inventory just like stockpiled forages offer standing feedstocks for grazing herds. Nobody brought hay to the bison. Pruning and weeding woodlots in the winter as part of an ongoing tree upgrade and open land soil-building program offers dormant season value. Too often farmers have periods of high income and low or no income; creating value off-season is one of the fastest ways to profitability.

An industrial chipper is expensive, but it can generate mountains of carbon in a hurry. Our Vermeer machine can create a cubic yard of chips in less than two minutes. Because we use these chips as bedding for all of our winter housed livestock, we use more than twenty tractor-trailer loads of chips per year. With this chipper, we can chip nearly two tractor-trailer loads in a day. We rent it out to others for a week at a time. Or a professional chipping crew could move from farm to farm like the threshing rings of yesteryear.

Shared equipment use is still viable. If we viewed our woodlots as fertilizer factories, we would spend more time managing them and take better care of them. Integrating them with open land is positive for both ecosystems.

I’ve done farm consulting where the senior farmer laments not enough income for a late-teenaged child who wants to stay on the farm. “This farm won’t produce two salaries,” Dad says. I look at the fertilizer budget and realize immediately that if the next generation were put in charge of the fertility program, the fertilizer savings would pay for another salary.

Investing in carbon through both forage and woodlot management is the fastest and cheapest way to grow soil. Soil is the ultimate wealth reservoir of a culture. Let’s build it.

This article was published in the December 2021 issue of Plain Values Magazine. If you want the latest stories every month, subscribe to the magazine at plainvalues.com. As a special thanks, get 10% off your subscription with the code “GAB23”!

Joel co-owns, with his family, Polyface Farm in Swoope, Virginia. When he’s not on the road speaking, he’s at home on the farm, keeping the callouses on his hands and dirt under his fingernails, mentoring young people, inspiring visitors, and promoting local, regenerative food and farming systems.