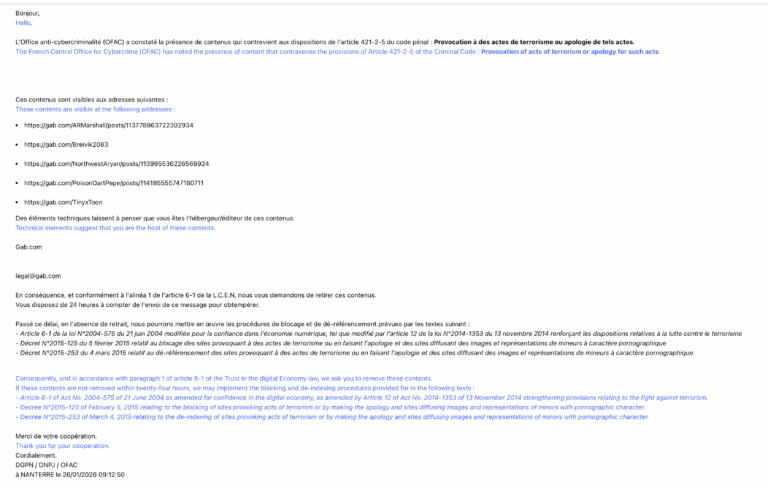

A blog post published today by a partisan political activist, who I will not name and will not link to, asserts that Gab’s refusal to provide subscriber data in response to foreign data requests is “phony.” e.g.

Jennifer Daskal, professor of law at American University, told Right Wing Watch that Gab’s claim that U.S. legal statutes prevented it from handing over non-content data such as IP addresses and subscriber information to foreign officials was untrue… Under the statutes, Gab is not required to disclose the information, but is also not forbidden from doing so.

Peter Swire, professor of law at Georgia Tech and research director for the Cross-Border Data Forum, explained that when it comes to turning over basic subscriber data, there’s no prohibition in U.S. law.

As usual, partisan outfits are more interested smearing and no-platforming Gab than they are in the truth.

We appreciate these academics’ views on the subject, but would caution them that we grapple with these issues on a daily basis and have some actual skin in the game. We also care deeply about our users and go to great efforts to protect their privacy, most especially dissidents in authoritarian countries with draconian speech laws.

It’s not theory or some academic paper to us, it’s real people who place real trust in us. Gab is better placed to understand our ongoing compliance risks, which are handled by world-class attorneys who have dealt with these issues in the real world for decades, than any academic.

Gab believes the Stored Communications Act does not permit wanton data disclosure to foreign governments

Gab’s position is that most U.S. companies have misread the requirements of the Stored Communications Act as it pertains to foreign government disclosures. Our view is that the intent of Congress was that the wanton voluntary disclosure of U.S. user data to foreign governmental agencies, as we imagine that some of our larger competitors engage in, is not permitted.

Most internet companies think “Person” means “foreign government.” We don’t

It is our policy, in a non-emergency setting, to not provide subscriber records to anyone without a court order. 18 U.S.C. 2703(6) permits disclosure of subscriber records “to any person other than a governmental entity.”

“Governmental entity” is defined as a governmental entity of the United States, so, not a foreign government.

“Person” is defined in 1 U.S.C. 1 as “corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals.” Foreign government agencies are not on this list. Notably, 18 U.S.C. 2703(7) makes specific, separate provision for foreign governments: it states that disclosure to foreign governments is permitted “pursuant to an order from a foreign government that is subject to an executive agreement” between that government and the United States.

We believe most of the internet industry has misread 1 U.S.C. 1. Applying the inclusio unius rule of construction to 18 U.S.C. 2703(6), it seems clear to us that it was not the intent of Congress to include foreign states among its list of “persons.” This view is reinforced by the fact that specific provision for foreign government disclosure of subscriber records is made in 18 U.S.C. 2703(7).

In any event, being a U.S. company, even if other Internet companies’ liberal construction of 18 U.S.C. 2703(6) is correct, we would have the discretion to refuse inbound requests and place foreign governments on an equal footing with the United States. It is our policy to do this.

We believe it is morally right for all American internet companies to treat all of their users by American standards.

Despite the above, we maintain good working relationships with international law enforcement, are very attentive to their requests, and have standard protocols in place for dealing with inbound requests for subscriber data either on an emergency basis or pending receipt of a court order issued pursuant to a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty, or MLAT, procedure.

Requiring an MLAT in non-emergency situations accomplishes a couple of key user-protective objectives for us. The MLAT process allows foreign governments to route data disclosure requests to Gab through the U.S. government, in which case we would have the same robust and complete response for them as if the request had originated with the U.S. government.

First, it is easier for us to authenticate that requests under MLAT are legitimate, as the requests are officially presented to the U.S. Department of State and the Justice Department. We cannot verify the integrity of law enforcement around the world. Due to the strong procedural protections available to criminal defendants in America, however, we have a very high degree of trust in U.S. federal law enforcement apparatus.

Second, we know that a U.S. court is bound by the First and Fourth Amendments, so any court order – whether issued in a domestic U.S. matter or at the request of a foreign government under the applicable MLAT – will not be violative of our users’ privacy rights and, most importantly, their free speech rights.

“Offensive speech,” for example, is one hundred per cent legal in America but is unlawful in other countries. In one recent case, a foreign law enforcement agency asked us to suspend a user account due to the account “directing many [disparaging remarks] towards Donald Trump and Theresa May.” Such a request, from a U.S. law enforcement agency, if made under color of law, would be an unconstitutional prior restraint on speech in the United States. (Indeed, it would be a crime for any American law enforcement agency to make such a request of us, per 18 U.S. Code 242.) Accordingly we refused the overseas government’s request. We told the foreign LEA that if the situation was an emergency they should contact us immediately.

U.S. law enforcement requests also need to pass muster with an independent judicial magistrate, and there must be reasonable suspicion (in the case of a grand jury subpoena) or probable cause (in the case of a search warrant) before those orders will issue. Many European countries do not require this, and a simple determination by a police officer that communications disclosure is necessary – without any requirement for independent facts that evidence the commission of a crime and justify the intrusion – is enough in these countries to compel domestic communications providers to turn over data.

Third and finally, we do not verify the national identity of any user. Accordingly, when a foreign government requests subscriber data, we assume that the user is American and extend U.S. protection to that account’s activity.

We believe we strike the right balance between user rights and public safety.

When a U.S. court orders us to hand over data, we can be sure that there are reasonable factual grounds for us to do so and that our users’ First and Fourth Amendment rights are not being violated. Unlawful use of our site is aggressively policed and prospective unlawful users are promptly banned. In non-emergency situations we require a U.S. court order before we will provide user data. In emergency situations, such as the posting of violent threats, our normal zero-tolerance policies around emergency disclosure apply.