by Gabe Harder

Defining the Covenant

To this point, it should be clear that the “covenant with Hagar” is key to Wilson’s brand of soft supersessionism. What’s equally clear, however, is that this particular covenantal arrangement evades precise definition, and what elements have been made plain at times appear entirely incompatible with a historic Reformed covenant theology.

A historical reading of the “covenant with Hagar” is, of course, impossible. Although God makes prophetic promises to both Abraham and Hagar concerning Ishmael’s future, “nothing is clearer [in Genesis 16-21] than the singularity of the covenant God made with Abraham and the passing down of that covenant through Isaac and not through Ishmael. There is, thus, no Hagar covenant.”1 Paul simply does not teach that “unbelieving Jews are in covenant with Hagar.” The phrase used by both Wilson and Sumpter, “the covenant with Hagar,” appears nowhere in the passage. Paul is clear that his appeal to Genesis is allegorical; the covenant, therefore, is not with Hagar, rather Hagar is the covenant (Gal. 4:24).

Put simply, Hagar is the Old Covenant considered apart from its fulfillment in Christ. This is the plain reading of the text. Hagar is the covenant made at Mount Sinai and governing the present, earthly Jerusalem (vv. 24-25). The conflict between the Old Covenant of law and the New Covenant of freedom wherein the promise to Abraham has been finally realized is central to Paul’s argument throughout Galatians. That argument culminates in the allegory of chapter 4, where, as summarized concisely by John Stott, “the two women, Hagar and Sarah, the mothers of Abraham’s two sons, stand for the two covenants, the old and the new, and the two Jerusalems, the earthly and the heavenly.”2 Matthew Henry is particularly helpful here:

“These two, Agar and Sarah, are the two covenants, or were intended to typify and prefigure the two different dispensations of the covenant. The former, Agar, represented that which was given from mount Sinai, and which gendereth to bondage, which, though it was a dispensation of grace, yet, in comparison of the gospel state, was a dispensation of bondage, and became more so to the Jews, through their mistake of the design of it, and expecting to be justified by the works of it. For this Agar is mount Sinai in Arabia…and is in bondage with her children; that is, it justly represents the present state3 of the Jews, who, continuing in their infidelity and adhering to that covenant, are still in bondage with their children. But the other, Sarah, was intended to prefigure Jerusalem which is above, or the state of Christians under the new and better dispensation of the covenant, which is free both from the curse of the moral and the bondage of the ceremonial law, and is the mother of us all – a state into which all, both Jews and Gentiles, are admitted, upon their believing in Christ.”4

-M.Henry

The Old Covenant bore children for slavery, but not in the first instance because of unbelief. Rather, as described by Henry, the Sinaitic covenant was a dispensation of bondage:

“Now before faith came, we were held captive under the law, imprisoned until the coming faith would be revealed. So then, the law was our guardian until Christ came, in order that we might be justified by faith…I mean that the heir, as long as he is a child, is no different from a slave, though he is the owner of everything, but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by his father. In the same way we also, when we were children, were enslaved to the elementary principles of the world.”

Gal. 3:23-24; 4:1-3

Even Old Covenant saints who possessed the faith of Abraham were for a time under this bondage. According to Calvin, “Those holy fathers, though inwardly they were free in the sight of God, yet in outward appearance differed nothing from slaves, and thus resembled their mother’s condition.”5 This is because “though they were children of God and heirs of the kingdom of heaven just like ourselves, [they] were under tutors and governors…Their ceremonies were like bridles or cords preventing those who observed them from enjoying the liberty that we have today through the Lord Jesus Christ.”6 Turning to the state of the “present Jerusalem” he adds,

“What, then, is the gendering to bondage, which forms the subject of the present dispute? It denotes those who make a wicked abuse of the law, by finding in it nothing but what tends to slavery. Not so the pious fathers, who lived under the Old Testament; for their slavish birth to the law did not hinder them from having Jerusalem for their mother in spirit. But those who adhere to the bare law, and do not acknowledge it to be ‘a schoolmaster to bring them to Christ,’ (Gal. iii. 24,) but rather make it a hindrance to prevent their coming to him, are the Ishmaelites born to slavery.”7

It was possible to be a spiritual son of Sarah under the covenant of law, “for the law contains many promises of salvation which were fulfilled in the Lord Jesus Christ.”8 It was also possible to live under the bondage of Sinai while ignoring its telos, and so without the Jerusalem above for a mother. This means that the Hagar covenant did not begin in the 40’s AD; it was the experience of unbelieving Jews bound to the Sinai covenant throughout history, only now exposed as abject slavery. At the coming of Christ all the spiritual blessings promised by the law became the exclusive possession of the heavenly Jerusalem. The advent of the New Covenant emptied the Old of its substance, leaving “nothing but what tends to slavery” for those who remained. As Wilson explains, “The heir, when he is little, is bossed around just like a servant.”9 The New Covenant, however, separates servants from sons. Jesus Himself anticipates this fact when He reminds faithless Jews who claim Abraham as their father that “the slave does not remain in the house forever; the son remains forever” (John 8:35).

Paul can speak of Hagar in the present tense precisely because he is writing circa AD 40, during a unique time in which both covenant administrations overlapped: “In speaking of a new covenant, he makes the first one obsolete. And what is becoming obsolete and growing old is ready to vanish away” (Heb. 8:13). This is a feature of the New Testament’s covenantal landscape that I first learned from Pastor Wilson:

“We commonly assume that the formation of the Christian church in the first century was an abrupt lurch into a completely different order of things. In reality, the transition from the older administration to the new took almost half a century. Pentecost occurred around a.d. 30, and the formal judicial dissolution of the older Judaic worship occurred in a.d. 70 in the destruction of Jerusalem.”10

-DW

We can agree with Wilson that the Hagar covenant does not evaporate gradually over time. As a moniker for the Old Covenant, it was finally and climactically brought to a close in AD 70 along with the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple of the Jews. This is the significance of Paul’s appeal to Genesis 21: “But what does the Scripture say? ‘Cast out the slave woman and her son, for the son of the slave woman shall not inherit with the son of the free woman’” (Gal. 4:30). Wilson seemed to know this when he wrote in One New Man that “this transition from the old covenant to the new is the point where Sarah has borne her freeborn son, and the slave woman is divorced and put away.”11 As J. B. Lightfoot observes, “It is scarcely possible to estimate the strength of conviction and depth of prophetic insight which this declaration implies. The apostle thus confidently sounds the death-knell of Judaism…”12

Sumpter grants that “the Old Covenant vanished at 70 AD with the temple and sacrifices, meaning that the temple approach to God has entirely ceased,” but adds that “just as the Jews existed in exile during the Old Covenant without sacrifices or temple, they can continue to exist for centuries, and they have.”13 What guaranteed the continued existence of biblical Judaism during the exile, however, was the fact that despite lacking a temple and sacrifices the Jews in exile remained a people in covenant with God. The destruction of the temple in AD 70 did not in itself terminate the Old Covenant. If that were the case, we might be inclined to think the Old Covenant had resumed were certain Zionist factions to have their way and re-institute the temple sacrifices. The destruction of Jerusalem, rather, powerfully bore witness to the reality that the covenant had in fact vanished, just as Jesus’ and His Apostles said it would. One might argue (as Wilson does) that the dynamic of bondage to meritorious works remains for modern Jews; “until the world ends, there will always be those who live carnally in unbelief and those who live in faith, by faith, and unto faith.”14 What is simply indefensible, however, is the notion that the Old Covenant order typified by Hagar endures to the present.

If we’re going to insist on mixing biblical metaphors, it will be essential to compare like terms. Romans 11 speaks of the unbelieving Jews being cut off, Galatians 4 of their being cast out. On Wilson’s reading, the unbelieving branches broken off of Israel’s tree are then grafted into the tree of Ishmael and the covenant with Hagar. But this would be to divide what is analogous in each metaphor; cutting off and casting out signify the same reality. The bondage of Hagar is the state of the unbelieving natural branches prior to being pruned from Israel’s tree. Unbelieving Jews do not become sons of the slave woman upon being cut out of the covenant; they are cut out precisely because that is what they already are.

As Pastor Wilson has taught, “there are only two ways to come into a connection with the tree [of the covenant]—to grow on the tree as the vast majority of the Jews did, or be grafted on the tree as the first century Gentiles were.”15 Branches that grow on the tree, whether first century Jews or tenth generation Scots Presbyterians, are natural branches. In attempting to expand the analogy of Romans 11 Wilson has run up against the force of the preterist reading. There is no mechanism offered for keeping the pruned natural branches alive, yet it is indeed the “natural branches” (branches that grew on Israel’s tree, and not some “tree of Ishmael”) that will be grafted back in (Rom. 11:24). The clear implication being that both the pruning and regrafting of these same natural branches must happen in fairly quick succession, and not after a period of two millennia or more.

Wilson’s “covenant with Hagar” leads him to believe that “when the unbelieving Jews were cut out of the olive tree, they were not thrown onto a gigantic burn pile,”16 but instead survived God’s judgment on the Jerusalem below as a covenanted people. An imminent and fiery destruction, however, is precisely what the Scriptures themselves anticipate concerning the faithless Jews who persist in unrepentance:

“You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit in keeping with repentance. And do not presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father,’ for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham. Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.”

Matt. 3:7-10

Conclusion

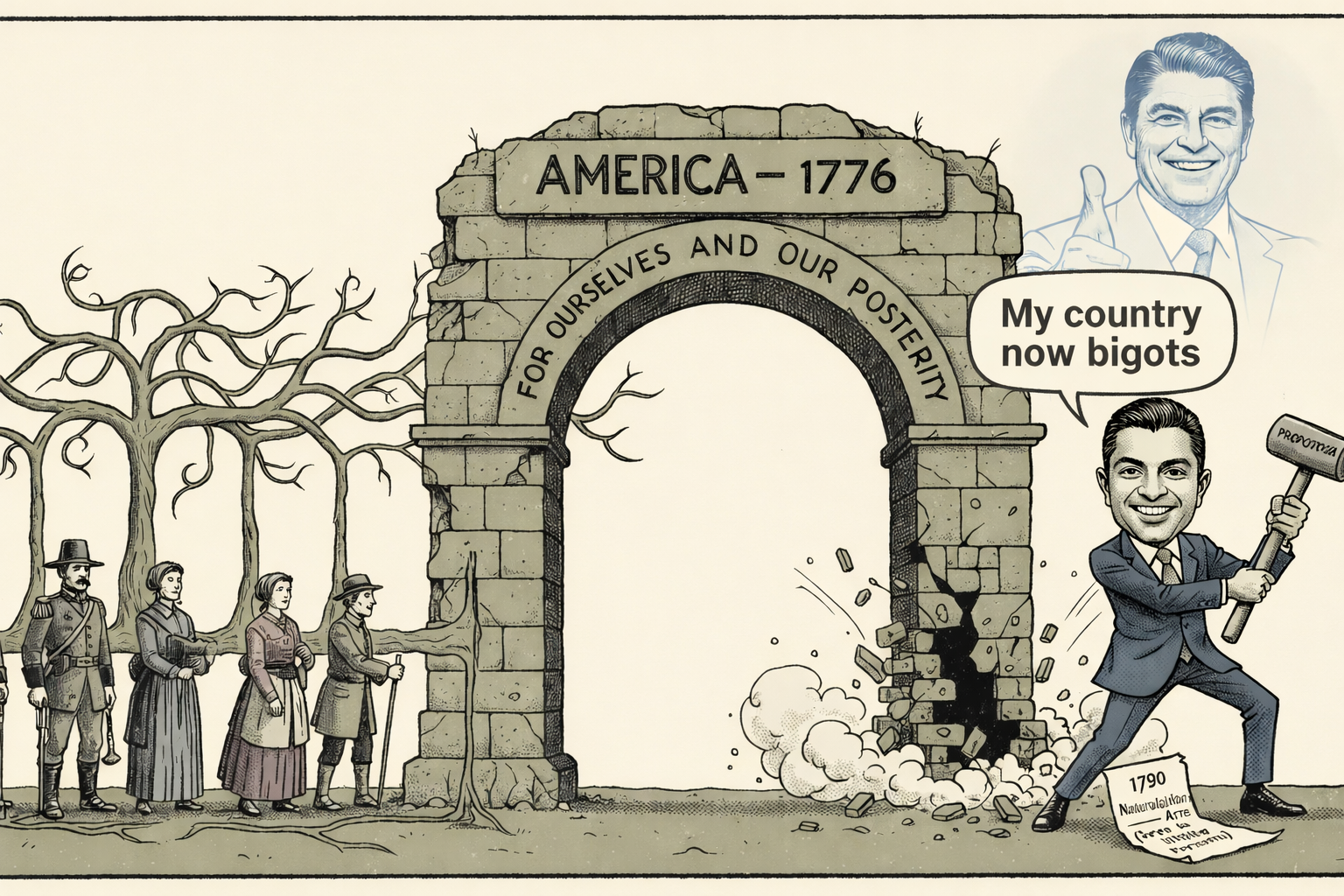

In a September blog post responding to Stephen Wolfe, Wilson invited anyone who would debate the merits of his proposed memorials on antisemitism and “ethnic balance” to “come at it with an open Bible…[and] make an argument grounded in Scripture.”17 I hope it’s clear that this is what I’ve attempted to do in responding to his reading of Galatians 4. While much remains to be said regarding American Milk and Honey, for now, suffice it to say that Wilson and company might garner more sympathy for his project if they ditched the “covenant with Hagar” angle in favor of an approach rooted in thorough exegesis and historic Reformed thought.

Gabe has a BA in Theology from Moody Bible Institute and is working toward an MA in Biblical Studies. He is a member and ministerial student at Christ Covenant Church of Chicago (CREC). He and his wife Sarah live in the Chicagoland area with their daughter.

FOOTNOTES:

- J. Louis Martyn, Galatians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 436.

- John R. W. Stott, The Message of Galatians (London: Inter-Varsity Press, 1968), 125.

- It’s clear that here Henry intends the present state of the Jews at the time of Paul’s writing.

- Matthew Henry, Acts to Revelation, Matthew Henry’s Commentary On the Whole Bible (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 1991), 539.

- John Calvin, The Epistles of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians and Colossians, Calvin’s Commentaries (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1974), 138.

- John Calvin, Freedom from the Bondage of the Law, Thirty Six Various Sermons. https://www.monergism.com/thethreshold/sdg/calvin/calvin_36sermons.html

- John Calvin, The Epistles of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians and Colossians, 138.

- Calvin, Freedom from the Bondage of the Law

- Douglas Wilson, To a Thousand Generations—Infant Baptism: Covenant Mercy for the People of God (Moscow: Canon Press, 1996), Kindle, Location 865.

- Douglas Wilson, One New Man: A Commentary on Galatians and Ephesians (Moscow: Canon Press, 2022), Kindle, 49.

- Wilson, One New Man: A Commentary on Galatians and Ephesians, 59.

- J. B. Lightfoot, St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians (Andover: W. F. Draper, 1870), 282.

- Sumpter, “Romans 11, Zionism, and the Future of the Jews.”

- Wilson, One New Man: A Commentary on Galatians and Ephesians, 59.

- Wilson, To a Thousand Generations—Infant Baptism: Covenant Mercy for the People of God, Location 1065.

- Wilson, American Milk and Honey, 101-102.

- Wilson, Douglas. “The Case of Owen and the Memorials.” Blog and Mablog (blog). 09/25/2023. https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/s7-engaging-the-culture/the-case-of-owen-and-the-memorials.html